Here’s your Sunday cuppa tea, or wine if you’d need for today’s juicy content: what has Google done wrong, for real?

Today let’s drink the richest blend—how they manipulated their auction mechanism to secure monopoly—according to the DOJ’s filed complaint.

Related blogs about DOJ vs. Google: DOJ’s complaints overview, and break down Part I and Part II.

before we begin, here’s a quick recap:

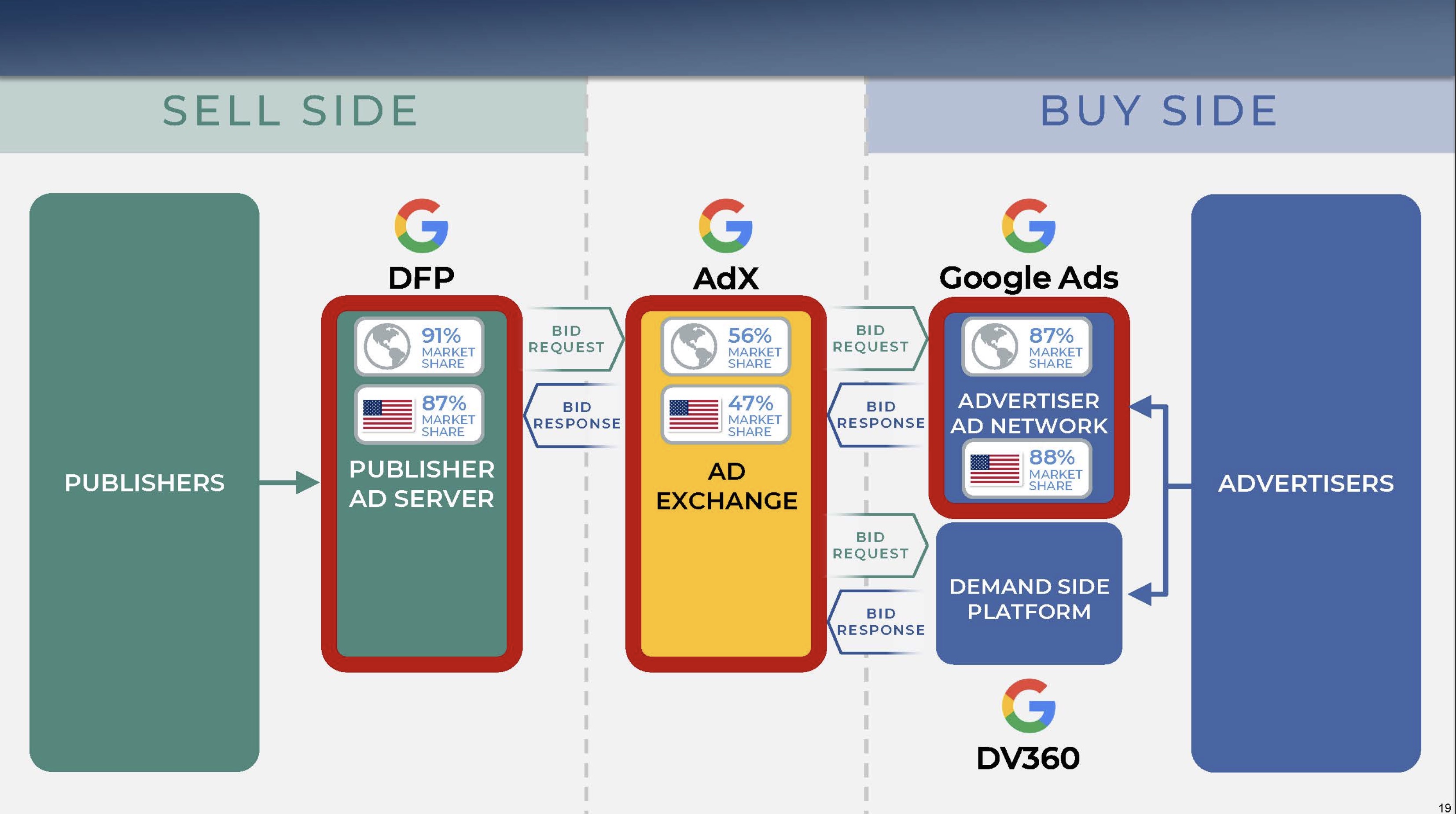

A quick look at the complete market:

The ‘ad-tech stack’, from the left (publishers) selling to the left (advertisers)

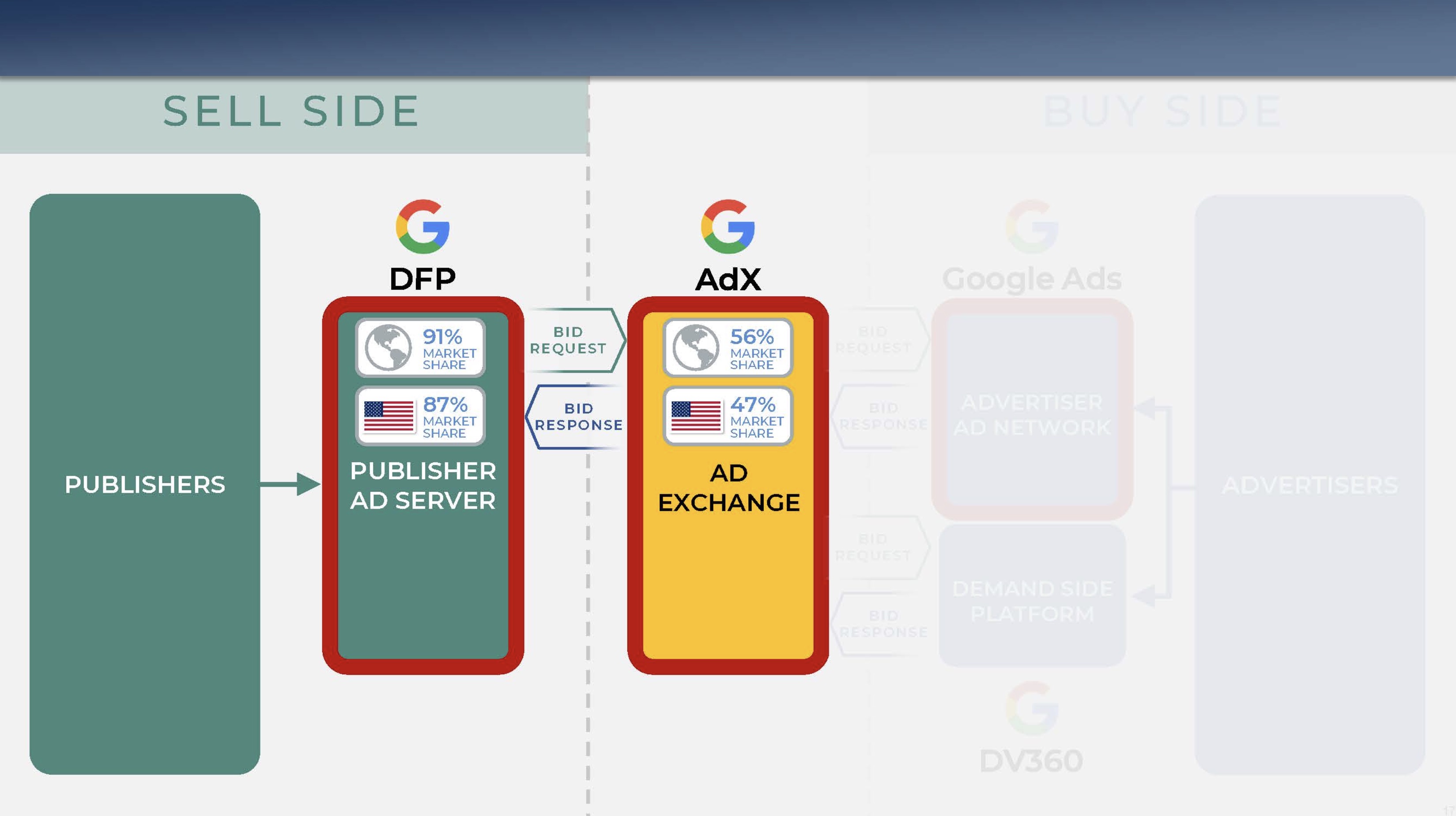

Today we focus on ad-exchanges, when they compete to buy impressions from publisher’s ad-server:

Today we focus on Ad server selling impressions to ad exchanges (and general buyers who purchase impressions, like demand-side platforms).

Google’s monopolistic maneuvers are mostly straightforward: acquire every piece of the vertical market puzzle—ad servers for publishers, ad exchanges in the middle, and advertiser buying tools (ad networks and demand-side platforms).

After monopolizing every vertical market, Google grants itself somewhat exclusive access. This primarily manifests in two ways: its advertiser buying tools favor Google’s own ad exchange, AdX, and its ad server, DFP, sells to AdX in an unfair manner.

Today’s discussion focuses on the latter—how Google’s monopoly ad server, DFP, sells its ad inventory (aka impressions) to multiple potentially competing ad exchanges. Our general storyline involves three stages of the selling mechanism:

- Era 1.0: Waterfall Auction – An almost obsolete sequential selling mechanism used by Google’s DFP to prioritize Google’s own ad exchange, AdX.

- Era 2.0: Publisher’s Fight-Back – Publishers introduce competition by implementing real-time bidding mechanisms (using HTML code in their headers) to sell to multiple ad exchanges.

- Era 3.0: Open Bidding – Google develops open bidding, a diluted real-time bidding auction run on Google’s own ad server.

All is fair in love and war, but not when the other side is the mechanism designer.

Sale Mechanism 1.0: Waterfall Auction

Here’s how it goes: Google’s ad server, DFP (DoubleClick for Publishers), managed ad inventory—those precious impressions on publishers’ websites sold to ad exchanges. Initially, Google’s DFP’s selling mechanism was a waterfall auction with a first-look advantage for Google’s ad-exchange buyer, AdX.

This sequential auction operated with a reserve price, where publishers specified a priority list of ad exchanges (or general buyers) based on historical prices and set a reserve price. Each ad exchange bids, if their price is more than the reserve price, they get the impression and the sequence stops—note, the buyers except Ad-Exchange does NOT know the reserve price.

First-Look Advantage

Since Google’s ad server (DFP) dominates over 80% of the market, and so does AdX—the main ad exchange—Google naturally favors itself. Specifically:

- Priority Listing: Google’s AdX is always first on the priority list.

- Informational Advantage: Unlike other ad exchanges that bid blindly, AdX has access to the reserve price and more cookie data, allowing it to better estimate the value of an impression.

As a result, AdX often purchases better impressions at lower prices, reinforcing its popularity on both sides and further entrenching Google’s monopoly.

Sale Mechanism 2.0: Header Bidding

When selling impressions, it’s obviously better to directly pick the highest-value bidder and sell to them, instead of inquiring one by one. Classical results from prophet inequality suggest that sequential auctions can lose up to half the potential value. Add Google’s preferential placement of AdX at the top of the sequence, and the inefficiency—and favoritism—further distorts the game and dampens revenue of the publishers.

Publishers want to make more money out of their ad inventories. What do you do if your ad server sucks? You build open, real-time competition by yourself:

header bidding

Header bidding worked as follows: publishers inserted certain computer code into the “header” section of the HTML code of a web page. This code triggered a real-time auction among ad exchanges before the publisher’s web page called the publisher ad server.

However, note that this “header bidding” is virtual—it’s a pre-auction that gauges the value of the ad exchanges to set a better reserve price.

Last-Look Advantage

Despite its benefits, header bidding requires Google’s ad server (DFP) to process the reserve price, and DFP share it with AdX exclusively—granting AdX a last-look informational advantage over rival ad exchanges. If even one advertiser in AdX is willing to meet the reserve price, AdX wins the impression.

The Crisis Brought by Header Bidding to Google

Despite header bidding being beneficial for publishers and potentially good for advertisers, Google saw it as a threat to its monopoly power. According to the DOJ’s filing:

…a 2016 Google internal presentation noted “header bidding and header wrappers are BETTER than [Google’s platforms] for buyers and sellers.”

In practice, header bidding dramatically improved the competitiveness of rival ad exchanges. By allowing a publisher to call multiple ad exchanges in real time—effectively multi-homing at the ad exchange level—header bidding vastly increased the amount of inventory rival ad exchanges could offer their advertisers.

Rival ad exchanges growing would not be good for Google’s peaceful reign. Even worse, some tech companies seized this opportunity and attempted to scale up the deployment of header bidding:

Building on the success of early client-side header bidding (where publishers write their own HTML code), several companies invested in developing innovative, free or low-cost tools (called “wrappers”) that enabled “server-side” header bidding.

This new form allowed the header of a web page to call a single server, which then sent requests to multiple ad exchanges. Each ad exchange returned a bid to the server, which in turn passed the winning bid to the web page. Server-side header bidding turbocharged the scale benefits by reducing integration costs and improving the user experience by lowering latency.

According to the DOJ’s investigation, Google viewed header bidding—and particularly server-side header bidding—as a direct and, in the words of a 2016 internal strategy paper, “existential threat” to its amassed market power.

Enough is enough. The market behemoth needed to take action to quell these “authoritarian intermediary” competitors. For real.

Sale Mechanism 3.0: Open Bidding

The good old days without competition for Google are over. If an auction is unavoidable, Google figured, “Why not be both the auctioneer and the bidder?”

Turns out, doing so would make things much easier. Google introduced Open Bidding:

Externally, Google portrayed Open Bidding as an improvement to header bidding that created a real-time bidding auction with multiple ad exchanges, similar to header bidding, but on Google’s servers to reduce latency.

But it turned out to be a Trojan horse smuggled into the innocent city of fair competition. Google sneakily manipulated Open Bidding to disadvantage rival ad exchanges in several ways, as accused by the DOJ:

- Transaction Fees: Google charges fees on every transaction over Open Bidding runned on Google’s ad server (DFP).

- Bid Restrictions: Google prohibites ad exchanges’ own advertiser-buying tools from bidding in Open Bidding auctions while allowing Google’s tools to participate.

- Information Control: Google takes “care” of the information flow during every transaction, hence maximizing their own informational advantage while minimizing the information access between publishers and rival ad exchanges—for example, only Google’s ad exchange, AdX, can see more cookie information and, vitally, the bids of other ad exchanges.

Come on, in a sealed-bid auction, isn’t everyone supposed to play fair and not peek at others’ bids? But Google seems to have found the auctioneer’s secret decoder ring. Despite more competition in the era of open-bidding, Google still is the gatekeeper of its AdX’s monopoly power in the ad exchange market.

Lastly, the DOJ summarized Google’s actions in solidifying its monopoly:

(a) Google Develops So-Called Open Bidding, Its Own Google-Friendly Version of Header Bidding To Preserve Its Control Over the Sale of Publisher Inventory

(b) Google Further Stunts Header Bidding by Working to Bring Facebook and Amazon into Its Open Bidding Fold

(c) Google Manipulates Its Publisher Fees Using Dynamic Revenue Sharing in Order to Route More Transactions Through Its Ad Exchange and Deny Scale to Rival Ad Exchanges Using Header Bidding

(d) Google Launches Project Poirot to Manipulate Its Advertisers’ Spend to “Dry Out” and Deny Scale to Rival Ad Exchanges That Use Header Bidding

(e) Google Imposes So-Called Unified Pricing Rules to Deprive Publishers of Control and Force More Transactions Through Google’s Ad Exchange

(f) Google Outright Blocks the Use of Standard Header Bidding on Accelerated Mobile Pages

(g) Google Replaces Its Last Look Preference from Dynamic Allocation with an Algorithmic Advantage and Degrades Data Available to Publishers

And the last piece of the puzzle is complete, revealing the full map of Google’s monopoly.

reference

U.S. Department of Justice, Antitrust Division. (2023). U.S. and Plaintiff States v. Google LLC [2023] - Trial Exhibits. Retrieved from https://www.justice.gov/atr/us-and-plaintiff-states-v-google-llc-2023-trial-exhibits

U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs. (2023). Justice Department Sues Google for Monopolizing Digital Advertising Technologies. Retrieved from https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-sues-google-monopolizing-digital-advertising-technologies