Finished reading the paper Suspense And Surprise finally. Honestly, the paper itself is already a masterclass of organizing contents so as to achieve high informational utility. Following what we left yesterday, here’s the rest, and some closing thoughts before the end.

Illustrations of Suspense-Opt. Info Policies

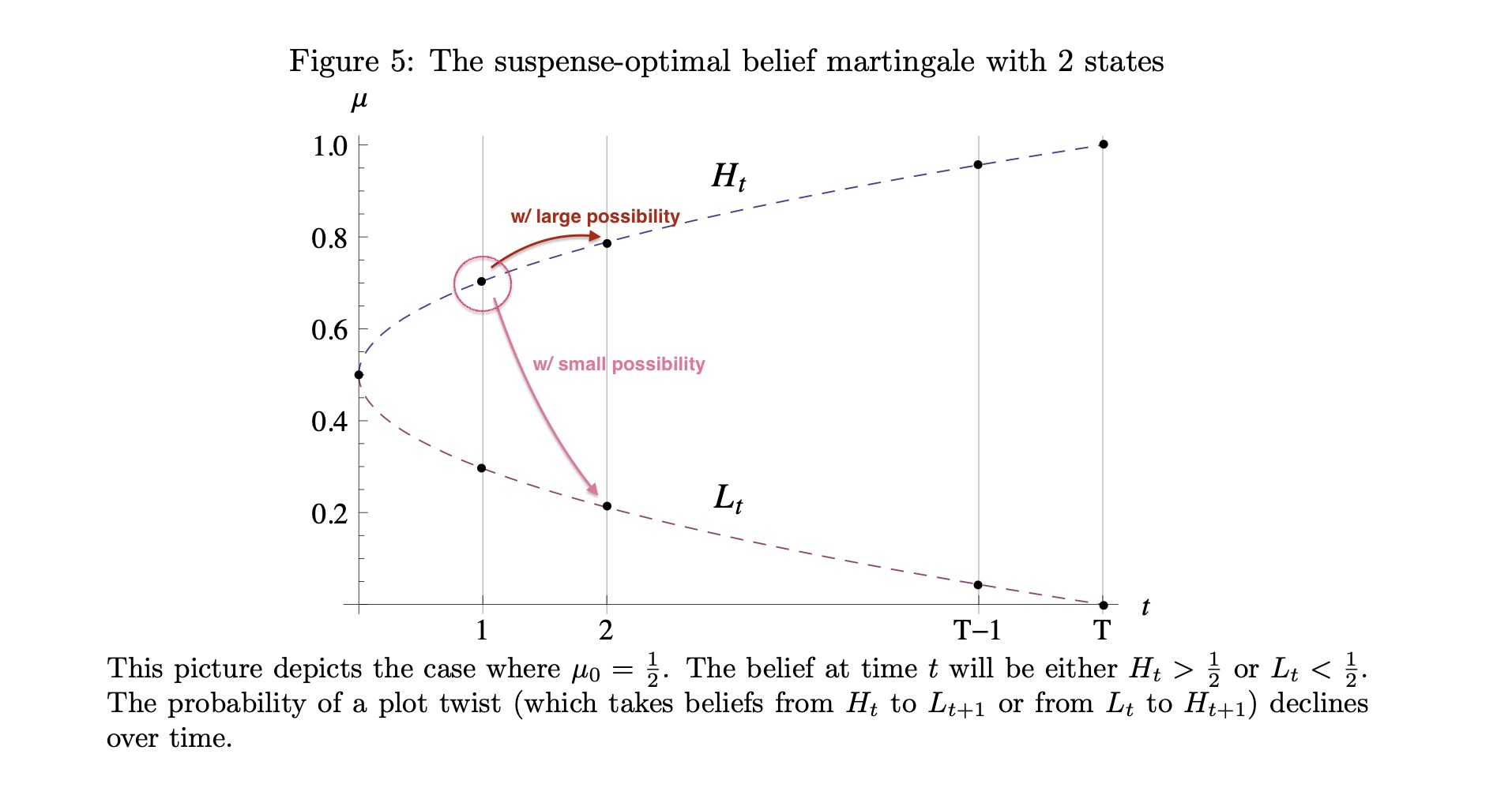

In the simplest setting where there are only two states $\Omega = {A, B}$ (i.e. whether AGT or FRA would win in the world cup final), suspense maximizing belief martingale give rise to the followig dynamics. Say, starting from initial prior$\mu_A = \mu_B = 0.5$, at period $t$ the optimal belief (say, WLOG let’s consider one side of the world, $\mu_t \equiv \text{Pr}(A)$), either takes a high value $\mu_t = H_t > 1/2$ or low value $\mu_t = L_t = 1 - H_t$. Stepping onto the next period, there are two possible changes to the new belief $\mu_{t + 1}$ - with high possibility the agent observes additional confirmation - that the higher(lower) belief gets “confirmed” a little bit further, like $H_t \to H_{t +1}$ where $H_{t + 1} > H_t$ and vice versa for $L_t$. Alternatively with small possibility, a plot twist happens, $H_t \to L_{t + 1}$ and vice versa for $L_t$.

borrowing a pic from the original paper. in the OPT. suspense martingale, towards next period, belief (circled dot) either stay and strenthen its belief with high possibility, or jump to another extreme with small possibility.

With three or more states, there is additional flexibility in the design of the optimal info policy (that maximize suspense). Consider A Study in Scarlet (Dole, 1887), suspects could be a bunch of people, and the author may maintain everyone’s suspicious until the end or rule out some of them during the middle. So there the alive-til-the-end policy, no clue rules out anyone’s until the last chapter. But sometimes sequential elimination can also work, where one of the probabilities is quickly taken to zero. For example, when one of the suspects got killed in the middle of the story.

Surprise-Opt. Info Policies.

While suspense-optimal policies have some clean characterization, solving for the surprise-optimal martingale is difficult in general and, in contrast to the case of suspense, sensitive to the choice of $u(·)$. Focusing one two-state setting, consider a specification where surprise in period $t$ equals $|\mu_t - \mu_{t - 1}|$ where once again $\mu_t \equiv \text{Pr}(A)$.

Then, by letting $W_T(\mu)$ be the value function of the surprise maximizing problem, where $T$ is the number of periods remaining, $\mu$ the current belief, we can express it via DP: $$ \begin{align} W_T(\mu) & = \max_{\tilde \mu’ \in \Delta(\Delta(\Omega))} \mathbb E_{\tilde \mu’}[|\mu’ - \mu| + W_{T-1}(\mu’)]\cr & s.t. E_{\tilde \mu’}[\mu’] = \mu\text{ (committment constraint)} \end{align} $$ And, some properties of the solved opt. info policy:

The single-period problem can always be solved by some $\tilde \mu’$ with binary support. Like, for any current belief, there is a surprise-maximizing martingale such that next period’s belief is either some $\mu_l $ or $\mu_h$.

But the optimal information policy accepts a positive probability of early resolution in return for a chance to move beliefs back to the interior and set the stage for later surprises. Also unlike the suspense solution, uncertainty can both increase or decrease over time. Realized surprise is stochastic, and beliefs might move early to degenerate (fully revealed), or moving back to initial belief.

Comparing Two Optimal Policies with an Analogy

While no existing sport would induce the exact distributions of belief paths we derive, we can think of soccer and basketball as representing extreme examples of sports with the qualitative features of optimum suspense and surprise.

In any given minute of a soccer game it is very likely that nothing consequential happens. Whichever team is currently ahead becomes slightly more likely to win (since less time remains). There is a small chance that a team scores a goal, however, which would have a huge impact on beliefs. So, belief paths in soccer are smooth, with few rare jumps. This sustained small probability of large belief shifts makes soccer a very suspenseful game.

In basketball, points are scored every minute. With every possession, a team becomes slightly more likely to win if it scores and slightly less likely to win if it does not. But no single possession can have a very large impact on beliefs, at least not until the final minutes of the game. Belief paths are spiky, with a high frequency of small jumps up and down; basketball is a game with lots of surprise.

Constrained Info Policies

I think this is where surprise of the paper comes in - that this part, seemingly boring at first sight (that I wasn’t even prepared to read it), turns out to be very interesting. Basically, there are often institutional restrictions (OK, whatever it is) which impose constraints on the information the principal can release over time. Examples include

Tournament Seeding:

Consider the problem of designing an elimination tournament to maximize audience interest. The planner(mechanism designer?!)’s job is to properly design the buckets of groups and seed teams into respectively one of them.

The simplest example is that, when there are three teams and two teams play in a first round and the winner plays the remaining team in the final. This remaining team is said to have the first-round “bye.” When the teams are assymetrical, which team should have the bye?

Sequential Contests

Example is president election - when the two parties want to winning over states. But, in what order should the states vote if the goal is to maximize the suspense or surprise of the race?

A more exciting primary season may elicit more attention from citizens, yielding a more engaged and informed electorate. In order to highlight the relevant mechanisms, our analysis here will assume that the order of the primaries does not affect the likelihood any given candidate wins.

We model a primary campaign as follows. Two candidates, A and B, compete against each other in a series of winner-take-all state primary elections. State $i$ has $n_i$ delegates and will be won by candidate A with probability $p_i$. The probability A wins each state is independent. Candidate A wins the nomination if and only if she gets at least $n^\star \in [0, \sum_i n_i]$ delegates.

So far, it seems that, since early states are sure to impose a small but positive impact on beliefs about the nominee, whereas late states have some chance of being extremely important and some chance of having zero impact. Then, to max surprise or suspense, should swing states go first or smaller or more partisan states should go first?

And the paper has this cool result:

Remarkably, for any distribution of delegates ni, for any set of probabilities $p_i$, for any cutoff $n^\star$, the order of the primaries has no effect on expected suspense or surprise. Small or large states, partisan or swing states – they may go in any order.

A Little Words

There are some more generalizations at the end of the paper, that the author brought up and relates with, I think, one of their subsequent work on characterizing informational uncertainty. In my point of view, there are some potential for computational study to step in here. I’ll leave it here, to play a little trick of suspense, and lack of closure.