The platform economy is indeed a formidable force, and this assertion is not without merit.

Yesterday, after watching a routine Premier League match featuring Manchester City, I experienced a striking example of the platform economy’s impact. Around 00:05, when all public transportation had stopped running, I had no option but to order a Didi taxi, a service similar to Uber, to return to my dormitory. To my surprise, a driver quickly accepted my request, indicating that the demand was relatively low.

Once in the vehicle, feeling tired but I struck up a conversation with the driver. Instantly he began to…complain, stating that working as a Didi driver was not profitable. He revealed that his car was rented, which meant he had to remain an active driver, unlike those who owned their vehicles and could choose when to work. On a daily basis, assuming he covered approximately 350 kilometers, his operational costs, including expenses like meals, vehicle rental, and fuel, amounted to roughly ¥1.2 per kilometer.

As a benchmark, traditional taxi services in Shanghai charge ¥2.4 per kilometer, with a starting fixed fee of ¥14 for the initial 3 kilometers, and an increased rate of ¥3.6 per kilometer during nighttime hours. Didi’s platform, on the other hand, has more flexibility in pricing while immense market power. The money that a driver gets (net) is about 1.5~2.1. Didi serves as an intermediary, matching supply with demand and strategically controlling pricing to extract surplus from both drivers and passengers.

The process is somewhat similar to an online matching problem. When a consumer requests a ride and enters a virtual queue, the platform dispatches this request to a subset of available drivers, with the first driver to accept the request completing the journey. Didi prescribes the route, penalizing deviations from this course, and charges a fee similar to traditional taxi services.

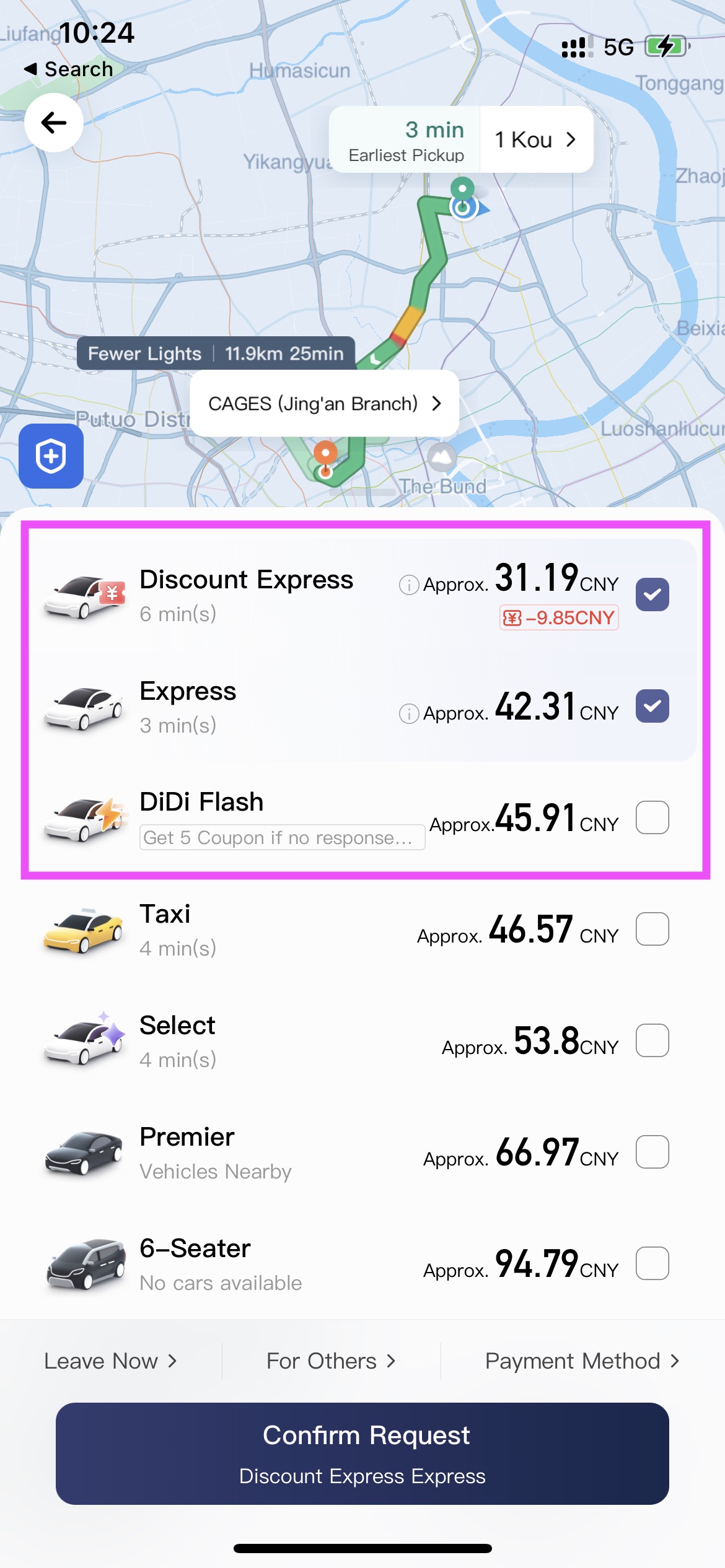

When ordered from the customer’s side, Didi offers multiple options with different prices. But the outlined pink ones, despite different in price, is actually the same. So they’re only different in terms of wait-time, potentially. Btw, benchmark traditional taxi price is ¥35.36, but the driver gets all.

Didi employs a variety of strategies. Notably, there are multiple service categories, including Discount Express, Express (the standard offering), and Didi Flash and so on. Interestingly, these categories (in pink outlined above) use the same types of vehicles, but they differ in pricing and potentially in queueing mechanisms hence wait-time. This variation in response times offers flexibility for both drivers and passengers to adapt to shifts in supply/demand and corresponding tradeoff between wait times and price.

Secondly, the process of matching, that is, the selection of drivers who compete for ride requests, is crucial. This aspect provides room for manipulation and can be seen as a big playfield for mechanism design, operations research, and economics. I believe that a significant team within Didi is dedicated to this endeavor. (Perhaps an internship opportunity beckons?)

Lastly, from a long-term perspective, Didi has the capacity to evaluate drivers and assign them “scores” based on certain metrics, incentivizing them to take on lower-priced services in the early stages to increase overall supply of oneself in a long run. Evidently, Didi has implemented this approach, as drivers who establish fresh accounts prefer fulfilling less lucrative orders to accumulate scores, leading to more profitable ride assignments exceeding ¥100 per trip. Drivers risk penalties if they decline too many low-value orders, which may result in a decreased rate of order allocation from the platform. It is unclear whether this assessment and discrimination mechanism is publicly disclosed to drivers, and even if it were, comprehending and navigating it remains a challenge. This dynamic resembles a repeated, online game, and it may currently be in an unfavorable Nash equilibrium for the drivers.

OK, back to reality, here’s some facts I know and personal experience. Currently, more than 30 smaller platforms vie for a share of the market, attempting to claim a slice of the substantial pie. Didi, as the largest ride-hailing platform in China, maintains a dominant market share, turns a profit (as evidenced by its IPO on the New York Stock Exchange), and wields considerable market influence, albeit without a monopoly. Didi has indeed created employment opportunities and enhanced convenience in my life. Nevertheless, it is imperative to note that ride prices do not consistently translate to cost savings, and drivers contend with the cutthroat competition perpetuated by the platform’s voracity, making it increasingly challenging to earn a sustainable income.

The fare for my ride last night was ¥44.96, as I distinctly recall. The driver lamented the platform’s occasional practice of charging passengers more while remitting a reduced sum to the driver. In jest, I promised to display my fare at the conclusion of the ride when the driver marked the order as “completed.” On this occasion, the displayed fare was accurate. However, one must bear in mind that it was the dead of night. Had I opted for a traditional taxi, the fare would have been $(12.39 - 3) * 3.6 + 18 = 51.804$, with the entire amount going to the driver. In contrast, the ride-hailing platform’s pricing is more competitive, while simultaneously extracting over 30% of the fare. Furthermore, a disconcerting trend emerges as conventional taxi services are compelled to align with ride-hailing platforms in order to augment their customer base, thereby consolidating the platform’s market influence and propelling this trajectory towards an unenviable equilibrium.

I am shocked, I have no word.